|

The Art of Tommy Canning

by Jef Murray

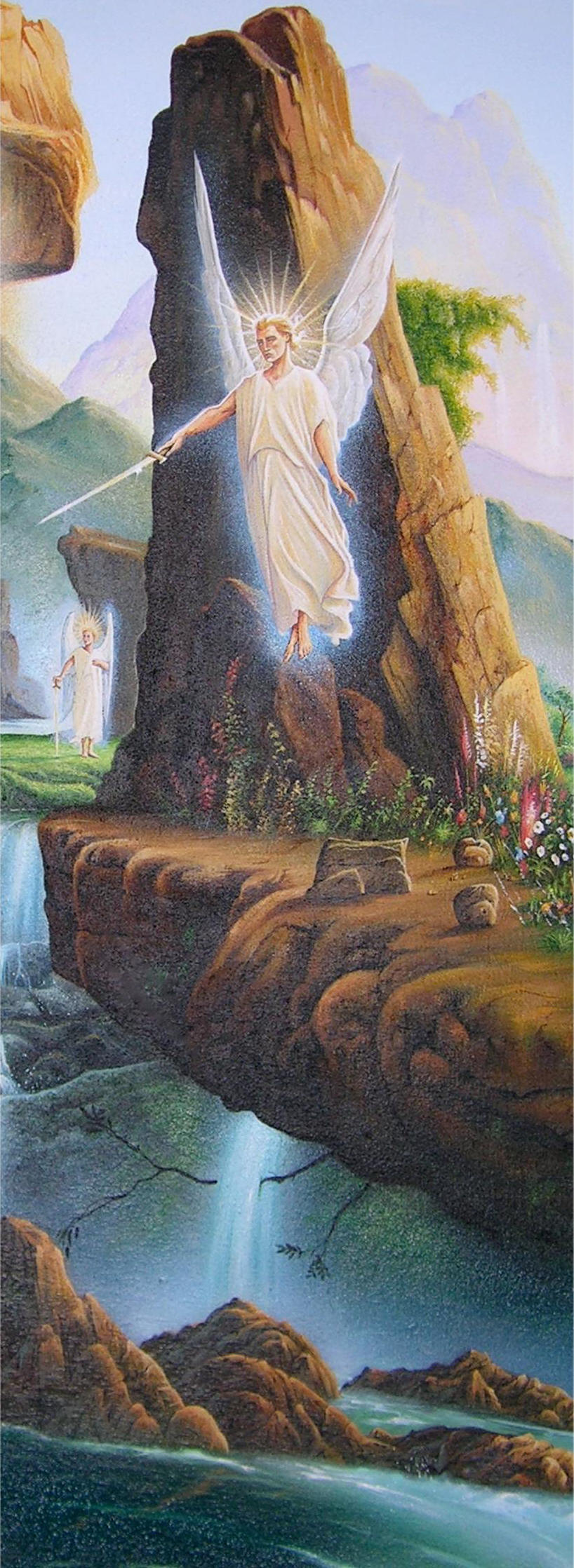

Tommy Canning’s

religious paintings are not for the faint of heart. And although many of

his images can be lyrical and charming, the overarching impression one

has when viewing his greatest works is of raw energy. Yet, this energy

serves a purpose. Canning’s work can be unsettling, but when that is the

case, it is for the sake of connecting the viewer with the deepest of

Catholic truths and with St. Faustina’s message of Divine Mercy. And it

does this in an almost visceral fashion.

Born to John and Mary Canning on Christmas day in 1969, the youngest of

five sons, Canning grew up in Scotland, south of the city of Glasgow. He

was just four years old when his father died of a heart attack. He went

on to suffer through difficult childhood illnesses, but was well formed

in the faith and benefited from the loving support of his mother and

brothers. Because he loved science fiction, fantasy, and comic books, in

his teen years, he decided he wanted to pursue art and illustration as a

career. But before he could get far in his formal training, his family’s

business failed and he had to jump headlong into trying to make a living

as a freelance illustrator.

“I managed to achieve some success, even before I had reached the age of

19,” says Canning. “At the same time, I began to reflect a lot more

about the kind of person I was. I began to ask myself the big questions

of life.”

“I realized that I was falling far short of what is expected of me as a

Catholic. I had never lapsed from attending church, but church was not

the center of my life. When I was 19, I visited Rome with my family — a

trip that changed my outlook and had a profound impact on me as a

Catholic and as an artist. I was simply blown away. I suddenly had the

desire to delve deeper into the Faith.

I also had a desire to

emulate the beauty and craft that was depicted in the art and

architecture of the churches in Rome.”

It was also about this time that Canning

became acquainted with the message of and devotion to the Divine Mercy,

as revealed to |

|

St. Faustina

in the 1930s. Born Helena Kowalska in Poland, this young girl entered

the Congregation of the Sisters of Our Lady of Mercy when she was almost

twenty, as a result of a vision she had of the suffering Lord. The

year following this vision, she received her religious habit and was given the name

Sister Maria Faustina. She went on to declare the desire that all the

world should know about Jesus’ loving mercy.

“Being an artist, I was also intrigued by Jesus' request of Sr. Faustina

in 1931 to have an image of Him painted according to the way He had

appeared to her,” says Canning.

“She saw

Jesus clothed in a white garment with His right hand raised in blessing.

His left hand was touching His garment in the area of the Heart, from

where two large rays came forth, one red and the other pale. She gazed

intently at the Lord in silence, her soul filled with awe, but also with

great joy.”

“Jesus said to her: ‘Paint an image according to the pattern you see,

with the signature: Jesus, I trust in You. I promise that the soul that

will venerate this image will not perish’ (Diary of St. Faustina, 47).”

“For me, this became like a call to use my artistic gifts that God gave

me to help make known this message of Divine Mercy.”

The Divine Mercy image is one of the paintings one encounters on

visiting Canning’s website (art-of-divinemercy.co.uk). It is one of the

more tame images, but it fixes a pattern for Canning’s subsequent work.

He creates intensely realistic scenes…sometimes almost to the point of

surrealism. And he uses light, lightning, the power of waves, and the

movement of planets to create an almost Promethean view of Christ as

fire-giver, as judge. But elsewhere, Canning shows us the Christ of the

Passion…Christ as victim and as profound carrier of all sin.

When first encountering Canning’s paintings, one may initially be

reminded of Renaissance paintings of the Passion, the Crucifixion, and

even of mythological events. Many of these have haunted the Western

subconscious for centuries. Who cannot help being deeply affected, for

instance, by Rubens’ painting of Prometheus, with the eagle tearing at

the flesh of the bound god? Yet it is just such a mix of visceral horror

and pathos that can at times grip one when viewing Canning’s Passion

paintings. In this, he may also remind the viewer of the cinematic

achievements of Mel Gibson’s “Passion of the Christ” (the soundtrack of

which magnificently compliments Canning’s images on his “Art of Divine

Mercy” DVD).

Again, these images can be tough to take. But Canning does not linger on

Christ’s sufferings without reason. Within some of his most graphic

works (e.g., “The Perfect Sacrifice,” a painting created to mark the

Year of the Eucharist) there are also images of hope, of joy, of the

deepest meaning of Christ’s offering of himself. The painting depicts

St. John and Our Lady in the foreground, gazing at the bloodied nailed

feet of Christ. But, beyond them both, in the background, we see Christ

at the Last Supper with his Apostles, instituting the Eucharist. And

around the whole, there is light in the form of a Jewish Menorah in the

upper left, with Trinitarian candles in the bottom left and right

corners. In the centre of all is a chalice with a glowing Host above

it…brighter than any other object in the whole image. Seemingly

handwritten texts in Greek adorn the top and bottom of the painting.

Canning explains. “The Gospel narratives from Luke’s Gospel at the top,

from Chapter 22:19 recall Christ’s words of institution with the

Apostles at the Last Supper. At the bottom of the image the words recall

the disciples’ encounter with the Risen Christ on the road to Emmaus,

Lk(24:31). Particularly the moment when Jesus breaks bread and their

eyes are opened.”

Some other paintings that take the viewer on very different journeys are

Canning’s “Before the Day of Justice” (relating to Divine Mercy), “Be Not

Afraid” (a powerful commemorative painting of John Paul IIs 25th

anniversary as Pope.), and “Creatio Ex Nihilo” (an 8ft by 5ft painting

of the creation of the Universe and the Fall of Adam and Eve, that is

installed in a retreat house in Spain).

The latter work is viewable online, but can be seen in greater detail on

Canning’s DVD. The image is enormous, and encompasses, in one place, the

first of God’s three great acts of mercy (Creation, the Incarnation, and

Sanctification/Divinisation, according to Canning). In “Creatio Ex Nihilo”, a luminous Father and Son with Holy Spirit between them are centred on the canvas amid exploding stars and planets. On their right

are Adam and Eve in the garden before the Fall, and on their left, the

couple reappear banished from the Garden. Viewing this painting in

person must be an awe-inspiring event, rather like the first unveiling

of Dali’s “Christ of Saint John of the Cross,” when allegedly many

attendees dropped to their knees in prayer. Canning’s work, especially

when viewed in DVD form by audiences at conferences worldwide, has

apparently had a similar effect.

"Creatio” exemplifies that aspect of Canning’s work which may be its

most important, and that is its unusual ability to connect classical

images with contemporary ones. One rarely encounters a creation scene

that shows planets and stars in the convulsions that 21st century human

beings understand to have been a part of the creation of our universe.

Yet here, Canning develops an image that can satisfy those who most

cherish traditional images of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, as well as

those who prefer the crisper, cleaner look of a motion picture or a

video game. A bridge has been created between the old and the new.

And with this, Gospel

truths become more real, more immediate, and infinitely less saccharine

in form than most of us are used to seeing in contemporary Christian

imagery.

In this respect, what Canning seems to have done is to make contemporary

Catholic imagery relevant. He has taken the truths of our faith and made

them almost palpable. And in so doing, he has taken to heart Pope John

Paul II’s 1999 letter to artists. In that magnificent plea to the

creative community, John Paul asserted that “it is up to you, men and

women who have given your lives to art, to declare with all the wealth

of your ingenuity that in Christ the world is redeemed….”

Tommy Canning has done this. He continues to struggle with the

difficulties of being a starving artist in an age that believes that

faith is irrelevant. But because of his vision and perseverance, we are

all blessed and strengthened. Because of his efforts, many souls that

might never have looked twice at religious art before may find

themselves believing once again in a God of

power and might.

Copyright 2007 Jef Murray,

Saint Austin Review.

This article first appeared in the May/June 2007 issue of StAR

Magazine and was written by Artist-in-Residence

Jef Murray (

www.JefMurray.com

). |